The future of payer regulation

A deep dive on our comment on CMS' proposed rule on interoperability and improving prior authorization

In December of last year, the CMS took the next step in its regulatory journey, putting out a press release regarding Advancing Interoperability and Improving Prior Authorization Processes Proposed Rule (CMS-0057-P). Like most regulation of technology, it will serve as a powerful catalyst for change that startups and incumbents alike should understand and build around. It is a rule that goes well beyond just prior authorization and contains a wide range of functionalities that benefit almost every role in the digital health ecosystem.

Given that some ink has already been spilled about the contents of that rule by a few authors (we recommend the Second Opinion write-up by Marissa Moore for a great overview), the thrust of today’s post is threefold:

Get out the comment - Demonstrate the simplicity of the federal comment process to remove perceived blockers for participating in the comment process. If we can do it, so can you. Let’s show how easy it is to comment and encourage participation.

Big Brain Energy - Highlight the insights we shared with the CMS in order to encourage others to join us in advocating for patient access.

Gritty Christopher Nolan-esque Reboot - the original posts on the newsletter here are dated, but we want to continue to share the things we learn and work on, such as this post, Dylan Klein’s Medical code systems for developers, or Angela Liu’s Navigating the maze of patient onboarding.

Mandatory “Who We Are” Section

As a reminder, since we’ve changed since first launching this Substack, Flexpa is the leading solution for embedded claims - allowing companies to use healthcare's financial data at the right place and right time. Whether powering new age strategic initiatives for cost management, quality improvement, and fraud detection or tactically focusing the population health and financial assistance of your patients, Flexpa's claims data modernizes legacy workflows and opens up entirely new possibilities.

Here is a great way to think of us: Flexpa’s most useful and differentiated feature is the capability to link clean, timely, identified claims data from a patient’s insurer. Other tools and mechanisms that provide claims data are often delayed weeks or months and are reliant on bespoke business agreements and attribution, whereas identified claims through Flexpa are available as soon as adjudication occurs, enabled solely by patient consent. Moreover, the Flexpa API offers a far more normalized claims data set than other routes, saving hundreds of hours of data science time.

You can see a detailed breakdown of our use cases here. Some great examples of folks who can use Flexpa right now (more detail in that doc) are Medicare brokers, bill negotiation companies, digital health providers, and health insurance carriers.

Background

While legislation generally gets all the focus and hype, it’s actually regulation that keeps the machine running. Our valiant government administrators use the divine authority granted by virtue of the (often brief and vague) laws our congresspeople create. Using that authority, they craft the actual rules of engagement for society’s operation. As put in “The Gang Explains Information Blocking: HIPAA”:

Since laws (and, maybe more importantly, the resulting administrative process) are inherently pretty confusing, we should start with a few definitions, as the various pieces are often mistaken for one another. It starts when Congress in its infinite wisdom passes legislation, as it is intended to do (although how well is much debated). Well-written law designates responsibility to a federal agency (or creates a new agency) to fill in the details of the legislation’s typically broad strokes. The agency then begins a rule-making process to create regulations (a/k/a implementation) with rules (a/k/a the steps of the regulations). Entities affected by these regulations’ rules interpret what they must do and enact organizational policy. Subsequently, the agency follows up from time to time with non-binding guidance (a/k/a advice to entities who have expressed confusion or skirted the meaning of the regulation).

Said another way - legislation is the law passed by Congress, which often gives broad authority to a federal agency to implement and enforce it. The agency then issues regulations, which are the detailed rules that specify how the law will be applied and what entities must do to comply. Regulations are legally binding and have the force of law. Sometimes, the agency also provides guidance, which is non-binding advice to help entities understand and follow the regulations.

Healthcare sits far up the bell curve of regulated industries, but authority is splintered across a few different federal agencies within the main agency tasked with protecting the health of all Americans, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS):

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC): This is the main agency people tend to think of, as the ONC coordinates nationwide efforts to implement and advance health information technology and electronic health records. The scope of their authority includes health technology vendors, providers, and health information networks.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS): As the nation’s largest payer, CMS has a large role in health technology through its reimbursement policies for medical devices and technologies, as well as the promotion of electronic health records and other health IT initiatives. Their regulation is limited to the groups that do business with them, so any providers that take CMS money or payers that have CMS-defined plans, such as Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and ACA.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA): The FDA is the primary regulatory agency responsible for ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of medical devices, including various health technologies. This can lead to some overlap with the ONC’s authority as the lines between health devices and software blur.

Office for Civil Rights (OCR): The OCR enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Rules involving the transmission, storage, or processing of protected health information. While they’ve had enforcement authority, the fines they can levy have been relative low stakes and the office is fairly small.

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) is an independent oversight entity within the HHS. Typically tasked with preventing fraud, waste, and abuse in HHS programs, the Cures Act recently gave it the statutory authority to issue up to $1 million in civil monetary penalties against health IT vendors found guilty of information blocking (although it has yet to finalize and wield this superpower)

However, many generations of overlapping and often contradicting legislation do not lend themselves to simplicity, so federal regulatory authority over some entities involved in healthcare exists outside the HHS:

Federal Trade Commission (FTC) - The FTC is an independent agency that promotes consumer protection and competition in the marketplace. The boundaries and contours of traditional healthcare authority stop with the walls of HIPAA. The vast unspeakable spaces outside where non-HIPAA entities like fitness and diet apps roam is wild and less regulated, but the FTC does offer some basic protections via regulation like the Health Breach Notification Rule. The FTC is also a main proponent of antitrust regulation via the Bureau of Competition, which impacts healthcare in this era of increased consolidation of providers, payers, and vendors. Many privacy advocates point to this area of authority as a gap in our national regulatory environment.

Department of Labor (DOL) - The DOL is primarily responsible for overseeing labor standards and workers' rights in the United States. Given that we have a tremendously unique and broken system of yoking healthcare insurance to employment, the DOL actually has regulatory authority over most commercial insurance plans. This mainly occurs through the Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA), who is responsible for administering and enforcing the provisions of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. As a result, holistic regulation of payers is surprisingly convoluted and fragmented.

These intricate cross-agency boundaries are one of the many forces that make the delicate dance of generating legal regulation so complex. Burdened with carve-outs and exceptions for marginally different scenarios, our regulators must construct the most nuanced incentives to affect change, but be careful not to overstep their legislative authority. They happen to be very good at this task - if they’re not, they get smacked around by the OMB (or shot down in court):

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) reviews and approves significant regulations proposed by federal agencies. This is done primarily through the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), a subdivision of the OMB. OIRA reviews proposed regulations to ensure they are consistent with the President's policy priorities, are based on sound analysis, and minimize regulatory burdens.

Health technology’s regulation has long been a good cop / bad cop story, with CMS playing second fiddle. During the era of Meaningful Use, Promoting Interoperability and Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), the ONC set the certification standards for EHR systems, while CMS administered the incentive programs and monitored compliance with meaningful use requirements.

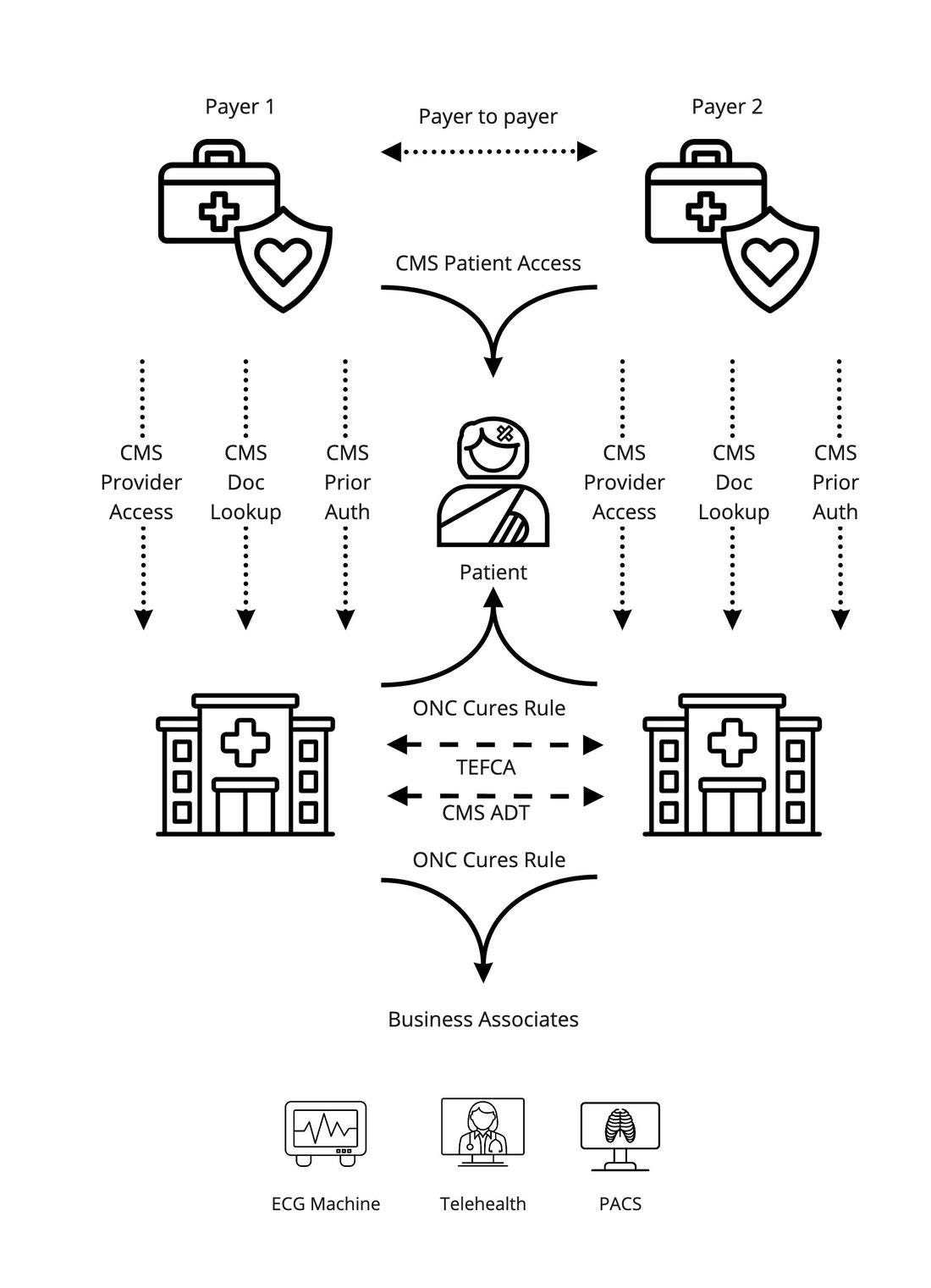

However, the CMS has moved to operate more independently and expand its own direct purview in recent years. Payers represent a huge regulatory blind spot in terms of technology adoption, given that the ONC has not had direct authority over them. The CMS, however, has major levers available to incentivize the behaviors it wants out of some payers. During the Trump administration, it began to flex those muscles, pushing payers to expose price transparency, provider directory, and patient access capabilities. As highlighted in the top half of this diagram from Health API Guy's Pondering the Health Policy Orb, the CMS has had a clear vision of extending this and stitching together the web of entities orbiting payers:

There are notably some gaps - in authority (CMS can’t regulate commercial plans), in compliance (state Medicaid agencies are laggard in adhering to rules), and in quality (many of the APIs can only loosely be defined as functional). But that doesn’t change the fact that this effort's ambition is remarkable. Within a decade, despite lacking any explicit legislative mandate, the CMS aims to overhaul the payer technology ecosystem, which has largely remained unaltered since HIPAA established X12 for claims exchange. It continues this effort with the new “Advancing Interoperability and Improving Prior Authorization Processes” Proposed Rule (CMS-0057-P).

Flexpa believes that other stakeholders and experts can more adeptly weigh in on the exact capabilities and timelines of the payer-to-payer, payer-to-provider, and prior authorization APIs. Providers and payers are acutely aware of the burdens and frictions inherent to their interactions today.

But as we sit in the liminal space between the last rule from the CMS and the finalization of the proposed rule ahead, it serves as a good vantage point to take the learnings from what we’ve seen and apply them to what’s to come. The focus of our comment letter was just that. We have strong conviction around our insights from connecting to the most payer Patient Access APIs of any organization today. Given that the proposed APIs are exponentially more complex than the patient access, provider directory, and cost transparency capabilities put into place today, the implementation pitfalls and non-compliance we see today will only be magnified tenfold without direct consideration in the new rule, threatening the success of the CMS’s goals.

We’re excited and hopeful that the final rule will address these considerations, as well as the many other comments other stakeholders left. Let us know what you think in the comments!

Thanks for reading the introduction! We hope you’ll enjoy the whole comment below, but before you do, make sure to subscribe!

Flexpa Letter

Background and Summary

This letter is in response to proposed final rule CMS-0057-P (the "Final Rule"). We support the principles and goals of the CMS Proposed Rule, especially regarding patient access to prior authorization decision information. The Proposed Rule aligns incentives across stakeholders and will be generally welcomed by payers as a means to streamline prior authorization decisions. In contrast to the Machine Readable Price Transparency Files, Provider Directory APIs, and Patient Access APIs, which some see as simple compliance burdens, the Proposed Rule has the potential to facilitate better decision-making processes.

However, for CMS to realize the full potential of these policies and ensure successful adoption and usage across payers and providers, we strongly encourage the addition of several missing policy details:

Identification of non-compliance

Enforcement mechanisms to encourage compliance

Clearer definition of data sets to be exchanged

Uniformity of capabilities across the industry

We believe that these should be addressed in the prior authorization rulemaking in order to ensure its success, as we detail below.

Identification of non-compliance

Payers have struggled with the relatively simple requirements of prior regulation. As of writing, 41 payers with populations served by a CMS-9115 regulated plan are known to be non-compliant with the Patient Access Rule with no active Patient Access API. In particular, at least 19 state Medicaid FFS programs do not have an available Patient Access API, with seven stating that they have no planned implementation. As a result, nearly 10 million Americans on Medicaid do not have access to their data.

The capabilities required to implement the various interoperability provisions of the Prior Authorization Rule are an exponentially more complex undertaking. Without efforts to reduce non-compliance, payers who struggled with implementing CMS-9115 will likely struggle with CMS-0057-P and overall levels of non-compliance will increase.

We recommend the implementation of a mechanism for parties to report payer non-compliance to the CMS in this rule. We believe that giving the CMS greater visibility into the state of implementation of rules and policies will enable the CMS to better design future policy.

Enforcement mechanisms to encourage compliance

With proper visibility of the state of compliance across regulated plans as listed above, we believe that the CMS also will want to ensure greater rates of compliance with CMS rule, ensuring the neediest Americans, such as Medicaid populations, have equal access to novel care navigation, financial assistance, and ultimately the right care at the right time.

We recommend that the CMS use all available tools within the constraints of its authority to guarantee its policies are implemented for all Americans. We recommend that the CMS define incentives that will drive compliance rates, such as penalties for non-compliance or increased payments for compliance.

Clearer definition of data sets to be exchanged

In the Patient Access Rule, the rule defined the data to be exchanged as:

Specifically, we are requiring that the Patient Access API must, at a minimum, make available adjudicated claims (including provider remittances and enrollee cost-sharing); encounters with capitated providers; and clinical data, including laboratory results (when maintained by the impacted payer).

The degree that this rule has been successful is heavily correlated with uniform access to FHIR resources such as Coverage, Explanation Of Benefit, and USCDI clinical data represented by the US Core IG. However, given the non-prescriptive nature of the data set definition, we have seen a variety of implementations excluding such core resources. For example, 12 payers do not provide a patient’s Coverage via the Patient Access API today. 5 payers do not provide a patient’s claims via Explanation Of Benefits via the API today, one of the core resources the CMS intended for patients to have access to and control of.

In the new Proposed Rule, the data set is even less clear, in that it excludes provider remittances and enrollee cost-sharing information from the Payer to Payer and Provider Access APIs:

"Specifically, that data exchange would include all data classes and data elements included in a standard adopted at 45 CFR 170.213 (currently USCDI version 1), adjudicated claims and encounter data (not including provider remittances and enrollee cost-sharing information), and the patient’s prior authorization decisions."

From discussions with implementers in the industry, we expect divergent implementations to only increase due to this ambiguity. Some implementers are exploring returning ExplanationOfBenefits scrubbed of the item level detail. Some implementers plan to exclude ExplanationOfBenefits altogether and only provide clinical data.

This requires use of HL7 FHIR Release 4.0.1, and complementary security and app registration protocols, specifically the SMART Application Launch Implementation Guide (SMART IG) 1.0.0 (including mandatory support for the “SMART on FHIR Core Capabilities”), which is a profile of the OAuth 2.0 specification, and the OpenID Connect Core 1.0 standard, incorporating errata set 1).

Furthermore, payer implementations of CMS-9115-F differ substantially in their conformity with SMART, OAuth 2.0, and OpenIDConnect. To take one example, at least 76 payer implementations of CMS-9115-F’s Patient Access API do not conform to SMART IG 1.0.0’s requirement to provide a patient launch context parameter when granting a patient/*.read scope.

We recommend that the CMS define more prescriptively a designated data set akin to USCDI for all intended capabilities. We recommend explicitly calling out the CPCDS in this rule. This will ensure more uniform implementation and ensure that patients, providers, and payers can use those capabilities in the way the rule intended.

We further recommend the CMS either define or promote the development of a conformance test suite on ONC’s Inferno. Machine validation has a two-fold benefit: (1) it reduces the burden on payer implementers by removing ambiguity, and (2) it reduces deviations between implementations. Together, these benefits will deliver improved rates of compliance of higher overall quality.

Uniformity of capabilities across the industry

In the initial CMS Patient Access rule, the CMS had indicated at various points the hope that payers would extend the technical capabilities defined by the rule to employer-sponsored plans, even though they were not explicitly included. For example:

We note that QHP issuers on the individual market FFEs are required under this final rule to implement the Patient Access API, and we encourage other individual markets, as well as small group market plans and group health plans to do so, as well.

We agree with the sentiment that the industry would benefit immensely from uniform deployment of the various interoperability capabilities of cost transparency, provider information, patient access, and prior authorization that the CMS hopes to promote, regardless of plan type. We note that as of writing, only 5 payers - Anthem, Capital District Physicians' Health Plan, Healthfirst, Kaiser Permanente, and UPMC - have implemented these capabilities for non-regulated populations.

We agree that current CMS authority unfortunately does not extend to private market health benefit plans and that direct regulation of those plans would be a function of and require collaboration with the Department of Labor’s Employee Benefits Security Administration (EBSA). However, CMS does have explicit authority over group health plans via public sector COBRA. By requiring plans offer public sector COBRA to offer the Patient Access APIs for any plans serving the public sector, the CMS can further promote these capabilities with an already well-defined authority. We recommend that the CMS pursue this in this rule, in order to encourage payers to expand the covered populations beyond the regulated minimum and ensure all Americans benefit from these interoperability advances.

We look forward to a collaborative industry and government effort on the rollout of prior authorization capabilities across payers and providers nationwide.

Sincerely,

Andrew Arruda - CEO, Flexpa

Joshua Kelly, CTO - Flexpa

Thomas Hamilton, COO - Flexpa

Brendan Keeler - Head of Product, Flexpa